physicsatweb.com– At the quantum scale, nature doesn’t hand you a neat little path to follow. It gives you a spread of possibilities—more like a cloud of “could happen” than a single “did happen.” The Schrödinger equation is the rule that tells that cloud how to change with time.

Once you accept that particles behave like states instead of tiny billiard balls, the weirdness becomes less mystical and more… mathematical.

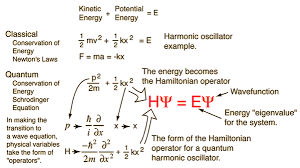

Why quantum physics starts with a wavefunction

Quantum mechanics uses a wavefunction, usually written as ψ (psi), to represent the state of a system. ψ isn’t a physical wave sloshing around in space like water; it’s a compact way to encode everything you can predict about outcomes.

The key move is probability: when you take |ψ|² (more precisely, ψ*ψ), you get a probability density. That’s how quantum theory links abstract math to what detectors actually register.

The schrödinger equation formula in one clean line

Here’s the standard schrödinger equation formula for how ψ evolves:

iℏ∂ψ∂t=H^ψi\hbar \frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t} = \hat{H}\psiiℏ∂t∂ψ=H^ψ

-

i is the imaginary unit

-

ħ (h-bar) is Planck’s constant divided by 2π

-

t is time

-

Ĥ (the Hamiltonian operator) represents the total energy: usually kinetic + potential

-

ψ is the wavefunction

If that looks like a compact “engine,” that’s because it is. Give it a Hamiltonian (your physical setup) and an initial state (your starting ψ), and it tells you how the state changes.

Time dependent schrodinger equation vs the stationary version

People often say “the schrodinger equation” like it’s one thing, but it comes in two closely related forms.

The time dependent schrodinger equation is the full evolution law (the one above). It’s what you use when the state is changing in time in a meaningful way—like a wavepacket moving, spreading, or reacting to a time-varying potential.

When the Hamiltonian doesn’t depend on time, you can separate variables and get the “stationary” or time-independent form:

H^ψ=Eψ\hat{H}\psi = E\psiH^ψ=Eψ

This version is about energy eigenstates (states with definite energy E). It’s the workhorse behind quantized energy levels in atoms, molecules, and many textbook problems. If you’ve heard of the schrodinger wave equation in the context of bound states, this is usually what people mean.

How you actually solve it (and why boundaries matter)

In practice, solving quantum problems is less about genius and more about setting up the right constraints.

-

Define the system: potential energy function V(x) (or V(r) in 3D), particle mass, geometry.

-

Write the Hamiltonian: commonly H^=−ℏ22m∇2+V\hat{H} = -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla^2 + VH^=−2mℏ2∇2+V.

-

Apply boundary conditions: wavefunctions must be finite, single-valued, and typically go to zero at infinity for bound states.

-

Normalize: total probability must be 1.

Those boundaries are where “quantization” sneaks in. Many systems only allow certain energies because only certain solutions satisfy the physical conditions. That’s not a philosophical statement—it’s math plus constraints.

What |ψ|² really buys you: prediction, not certainty

A common beginner trap is thinking quantum mechanics is “random” in a lazy way. It’s not. It’s probabilistic but precise.

If ψ is normalized, then |ψ(x)|² tells you how likely a measurement is to find the particle near x. You can compute expectation values too—like average position ⟨x⟩ or average energy ⟨E⟩—using operators.

So the theory doesn’t say, “anything can happen.” It says, “here is the distribution of outcomes, and here’s how it evolves.” That’s a very different kind of power.

Where this shows up outside textbooks

Even if you never solve a hydrogen atom by hand again, this framework is baked into modern technology and modern explanations of matter:

-

Atomic and molecular structure: why electrons occupy orbitals, why spectra have discrete lines.

-

Semiconductors: band structure and why materials conduct or insulate.

-

Tunneling: the reason scanning tunneling microscopes work, and a key effect in many electronic devices.

-

Lasers: quantized energy levels and controlled transitions.

Quantum mechanics can feel abstract until you realize it’s the reason solids have the properties they do.

One small “experience” insight beginners usually miss

When people first learn this, they often treat ψ like a picture and forget it’s also a constraint system. Tiny mistakes—like forgetting normalization, mixing boundary conditions, or using an energy eigenstate when the setup is time-varying—don’t produce “slightly wrong” answers; they produce completely unphysical ones.

Also: the Hamiltonian is the boss. If you don’t understand what’s inside Ĥ, you’re not solving physics—you’re just moving symbols around.

A quick aside about “rules” searches on the internet

If you’ve ever googled something and landed somewhere unexpected, you’ve seen how the word “rules” can spiral—sometimes into phrases like go fuck yourself card games rules. Quantum rules are at least cleaner: define the system, write Ĥ, evolve ψ.

The Schrödinger equation is the simplest honest statement of quantum motion: the state evolves smoothly, while measurements reveal outcomes probabilistically. Once you learn to read the Hamiltonian and respect boundary conditions, the “weirdness” turns into a dependable toolkit.